-

by Admin

15 February 2026 5:35 AM

“A Letter of Intent is but a promise in embryo, capable of maturing into a contract only upon fulfilment of conditions; it does not bind the State unless contingencies are met,” held the Supreme Court.

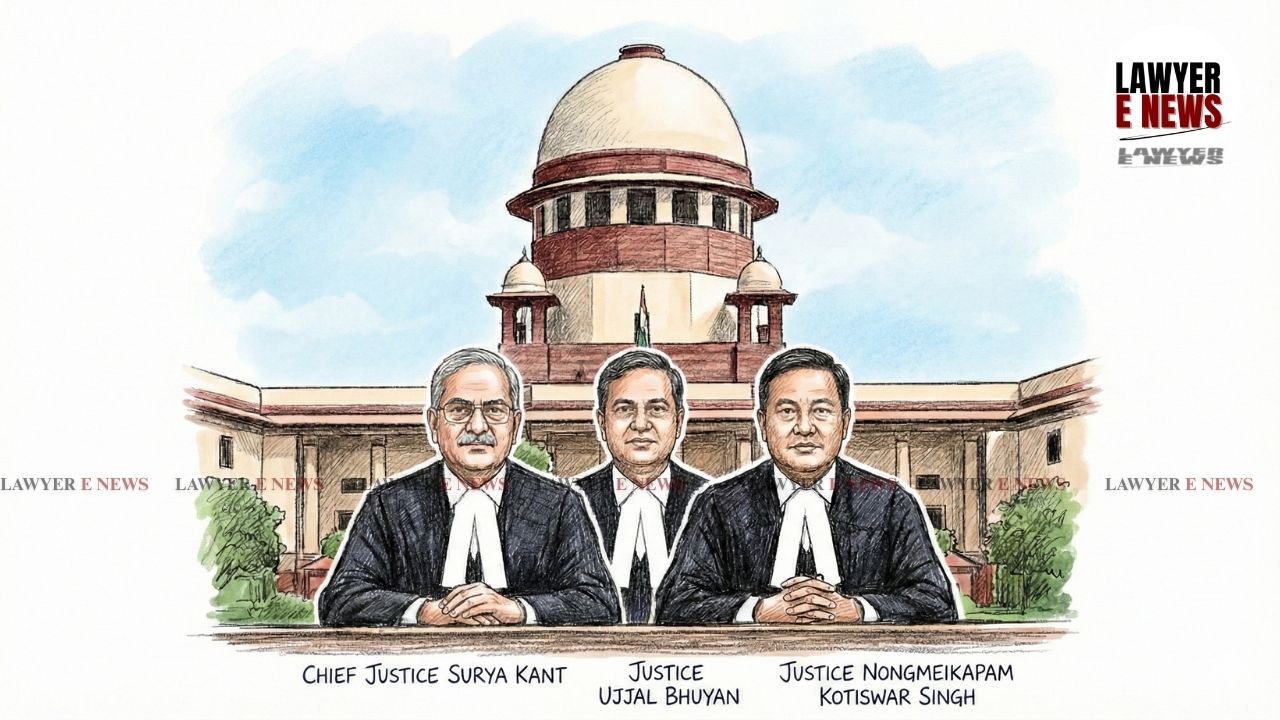

In a significant judgment delivered on 24 November 2025, the Supreme Court of India in State of Himachal Pradesh & Anr. v. M/s OASYS Cybernatics Pvt. Ltd. decisively ruled that a Letter of Intent (LoI) does not confer enforceable contractual rights unless it explicitly matures into a concluded agreement. The three-judge Bench led by Chief Justice Surya Kant, along with Justices Ujjal Bhuyan and Nongmeikapam Kotiswar Singh, upheld the State’s decision to cancel a conditional LoI for the supply of upgraded electronic Point-of-Sale (ePoS) devices, holding the move to be neither arbitrary nor violative of natural justice.

The apex court allowed the appeal filed by the State of Himachal Pradesh, thereby overturning the High Court’s judgment dated 30 May 2024, which had directed enforcement of the LoI issued in favour of the Respondent, M/s OASYS Cybernatics Pvt. Ltd., and had mandated restoration of contractual obligations.

“A bidder’s expectation that a contract will follow may be commercially genuine, but it is not a juridical entitlement.”

The principal legal issue before the Court concerned the binding nature of an LoI issued on 02 September 2022 to OASYS for the supply and maintenance of ePoS devices under the State’s Public Distribution System (PDS). The contract was designed to digitise Fair Price Shops using biometric and IRIS-enabled hardware, integrated with national Aadhaar-based systems.

The State, through senior counsel Mr. P. Chidambaram, contended that the LoI was expressly conditional, subject to four key preconditions: successful compatibility testing with NIC software, live demonstration before State authorities, execution of a formal agreement, and submission of a detailed cost structure. Despite reminders over an eight-month period, these conditions, the State argued, were never fully complied with. It also alleged technical incompatibility and suppression of material facts regarding prior blacklisting by the Respondent’s predecessor entity.

OASYS, represented by Mr. Sanjeev Bhushan, opposed the cancellation, asserting that its continued performance—including hardware manufacturing and pilot deployment—created a legitimate expectation of contract finalisation. The High Court had accepted this line of reasoning, deeming the cancellation arbitrary, unreasoned, and procedurally unfair.

However, the Supreme Court emphatically disagreed.

“Legality, not commercial disappointment, is the touchstone of judicial review under Article 14.”

Chief Justice Surya Kant, writing for the Bench, delivered a detailed exposition of the legal status of a Letter of Intent, reiterating longstanding precedent that an LoI does not amount to a concluded contract.

Citing Dresser Rand S.A. v. Bindal Agro Chem Ltd. and Rajasthan Cooperative Dairy Federation Ltd. v. Maha Laxmi Mingrate, the Court underscored that, “a letter of intent merely indicates a party’s intention to enter into a contract with the other party in future. A letter of intent is not intended to bind either party ultimately to enter into any contract.”

The Court found no ambiguity in the LoI issued to OASYS. On the contrary, the document had clearly stipulated that execution of the agreement was contingent on prior fulfilment of certain codal formalities and technical benchmarks. The Bench dismissed OASYS's reliance on subsequent correspondences and asserted that "commercial impatience does not substitute contractual compliance."

The ruling therefore concluded that no enforceable rights had arisen in favour of OASYS under the LoI.

“The State’s discretion to re-tender, grounded in documented non-compliance and public interest, cannot be struck down as arbitrary.”

On the second core issue—whether the cancellation order dated 06 June 2023 was arbitrary—the Supreme Court acknowledged the initial laconic nature of the cancellation letter but found adequate justification in the contemporaneous official records.

Referring to the guiding principles in Tata Cellular v. Union of India and Jagdish Mandal v. State of Orissa, the Court reiterated that judicial review in public contracts does not empower courts to substitute administrative decisions, unless shown to be irrational, mala fide, or perverse.

“We find that the Department’s decision to cancel the LoI was based on verifiable deficiencies,” observed the Court. Not only had compatibility tests not been certified, but the Respondent also failed to provide itemised cost break-up under Clause 4.9(m) of the RFP. Additionally, no live demonstration had been formally recorded.

The Court also rejected the plea of legitimate expectation, holding that “where conditions precedent are explicitly stated in the LoI, they negate any enforceable expectation.” Likewise, a past blacklisting complaint raised by a rival bidder—though not decisive—was found irrelevant since it had already been adjudicated by the High Court in earlier proceedings.

The apex court concluded that the State’s action was neither mala fide nor lacking in procedural fairness, and that its decision to invite a fresh tender was a “lawful exercise of administrative discretion”.

“No bidder has a vested right to be awarded a government contract unless the terms of the bid are fulfilled and the contract is executed.”

The Court, however, took a balanced approach by acknowledging the substantial preparatory expenditure undertaken by OASYS in anticipation of contract finalisation. While rejecting any claim for loss of profit or consequential damages, the Court invoked the equitable principle of quantum meruit.

The judgment directed the State Government to reimburse OASYS for the actual cost of deliverables supplied and services rendered during the pilot deployment phase, subject to verification. It also clarified that any equipment or software integrated during that period would vest with the State, free of encumbrances, upon payment of such assessed costs.

In allowing the State’s appeal, the Supreme Court reaffirms a critical tenet of public contract jurisprudence—that government discretion in tender matters is sacrosanct, provided it is exercised lawfully and rationally, and that pre-contractual instruments like Letters of Intent carry no binding force absent the execution of formal contracts.

The judgment strikes a delicate yet firm balance between upholding public interest and procurement discipline, while also ensuring equitable restitution to the aggrieved bidder for services actually rendered.

Date of Decision: 24 November 2025